The National Gallery, Buckingham Palace Gates, the house of David Lloyd George, the Epsom Derby, and The Monument to the Great Fire of London. What do these have in common? They were all battlegrounds of the Women’s Social Political Union (WSPU), better known as the Women’s Suffrage Movement, headed by the formidable Emmeline Pankhurst.

The events occurred at a very volatile time between 1913 and 1914: from protesting and leafleting to public speaking and even hunger strikes in prison, but it seemed nothing could sway the ruling Liberal Party, or the ‘man on the street’ to give women the vote. As Emmeline Pankhurst declared to a crowd in Cardiff in 1913: ‘Militancy was right because no measure worth having has been won in any other way.’

We don’t know if Miss Ethel Spark and Mrs. Gertrude Shaw had read the words of Mrs. Pankhurst in the weekly circulated ‘Suffragette Newspaper’, but something spurred them on when they decided to plan a protest of their own.

The day was Friday 18 April 1913, when the two women arrived at The Monument. The column towered over the City of London as it had for over two centuries before. The area, situated in what was then known as the ward of Candlewick, would have been a hive of activity. Old Billingsgate Fish Market was nearby at the bottom of the hill, and the hustle and bustle of London Bridge was just metres away.

At 10am, they ascended the 311 steps and managed to distract the two attendants who were stationed behind a small door at the top of the stairs and gained access to the platform. They slammed the door shut on the men and secured it using two iron bars they had smuggled in. That challenge now complete the protest could begin.

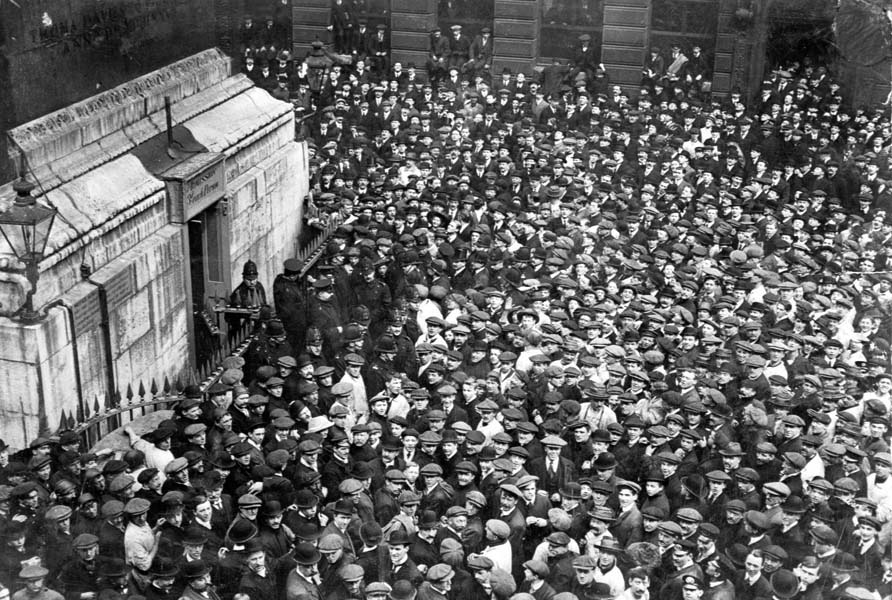

Onlookers gather outside The Monument with the City of London Police stood by the entrance. ©Museum of London

Miss Spark and Mrs. Shaw began by running to the flagpole. They hauled down the City of London flag and attached the now iconic purple, white and green cloth to the cord: these colours had long symbolised the Suffragette movement. They proudly hoisted the flag above the City and began to unfurl another long banner bearing the motto “Death or Victory”. It blew in the wind, tied to the outer railings. By then, the protest began to attract large crowds below them, with thousands of mostly male workers filling the piazza. People were cramming onto surrounding window sills, rooftops and porches to get a view of the pandemonium unfolding before them.

It was now time for their final move: Miss Spark and Mrs Shaw released hundreds of handbills to the crowd promoting the votes for the women cause. The crowds cheered and jeered in equal measure as the City of London Police arrived to put an end to the protest. With the help of a 12-pound sledgehammer, the police struck the door down, removed the banner and escorted the protestors calmly down the stairs to nearby Monument station.